Collaborative Robotics:

What is a Collaborative Robot?

Read the full Collaborative Robotics eBook:

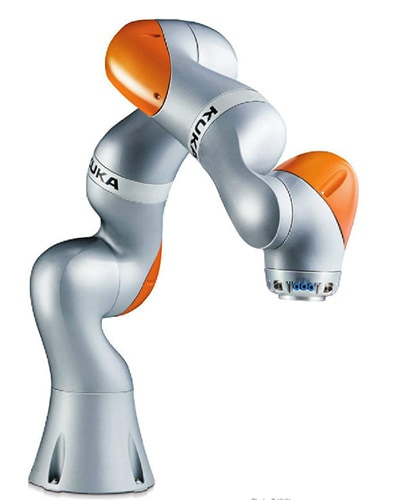

Title Image: KUKA’s LBR iiwa: LBR stands for “Leichtbauroboter” (German for

lightweight robot), iiwa for “intelligent industrial work assistant.”

By Steven Keeping for Mouser Electronics

Large, heavy industrial robots are commonplace in factories as a more efficient alternative to manual workers for

repetitive assembly-line tasks. The machines never slow down, never make mistakes, and never require time off. Yet

they are expensive and inflexible, demanding time-consuming reprogramming and retooling to switch to new tasks. This

makes industrial robots suitable for high-volume, high-speed processes where a product is produced for years without

change: Automotive chassis welding is a classic example of this.

Humans are not so good at highly-repetitive tasks because they tire and lose concentration. But humans are

dexterous, flexible, and good at solving problems. And human labor is relatively inexpensive. This makes humans well

suited for complex, high-mix assembly jobs, such as fitting an auto’s interior with multiple options that a

customer chooses.

Collaborative robots are light, inexpensive industrial robots designed to fill in gaps by working closely with

humans to bring automation to tasks that had previously been completed solely with manual labor. Robots offer

significant productivity gains while humans focus on servicing a rapidly changing product mix: Ultimately proving

that “collaboration” works. A study conducted by Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) researchers

at a BMW factory showed that human idle time was reduced by 85 percent when they were assisted by collaborative

robots.

The applications for collaborative robots are numerous and varied. For example, a collaborative

robot could pick up a heavy dashboard from a storage area located near the auto line and move the dashboard into its

proper place for production, at the same time a human can be working to fit or blank off dashboard switches, make

the “awkward-to-reach” electrical connections, and precisely align the instrument console before fixing

it into place. Collaborative robots are also finding work in places like smartphone assembly lines where picking,

gluing, and pressing operations are completed by the machine while human workers fit circuit boards, screens, and

batteries all before fixing the components together with tiny screws. According to the automation firm ABB, 90

percent of today’s collaborative robots work in consumer electronics factories.

Collaborative robots are smaller, lighter, and cheaper than their industrial cousins, measuring tens of centimeters

rather than meters, weighing in at 10kg rather than a hundred, and costing tens of thousands of dollars rather than

hundreds of thousands. Collaborative robots borrow some technology from their larger cousins, such as motors and

joints, but this technology is refined, streamlined, and shrunk. Programming is much simpler than that required for

an industrial robot and is sometimes as simple as manually guiding a robot’s arm through the procedure: This

is so simple it can be performed by a coworker rather than a robot specialist technician. Maintenance is simple so

smaller companies with no previous robotics expertise can manage it. And because collaborative robots share the same

workspace with humans, they contain sensors and computing power to ensure coworkers aren’t bashed by

artificial arms, and if human and robot contact does happen, the forces involved are limited to prevent harm.

The collaborative robot sector holds much promise. Today, the machines bring automation to assembly tasks that were

previously completed by humans, freeing up those workers to concentrate on more intellectually-rewarding jobs.

Tomorrow, collaborative robots could ensure that production lines keep running in places where inexpensive human

labor is in short supply. This promise, according to UK analyst Technavio, will see the market for collaborative

robots expand tenfold, jumping to over $1 billion in as little as the next two years.

Steven Keeping is a contributing writer

for Mouser Electronics and gained a BEng (Hons.) degree at Brighton University, U.K., before working in the

electronics divisions of Eurotherm and BOC for seven years. He then joined Electronic Production magazine and

subsequently spent 13 years in senior editorial and publishing roles on electronics manufacturing, test, and design

titles including What's New in Electronics and Australian Electronics Engineering for Trinity Mirror, CMP and RBI in

the U.K. and Australia. In 2006, Steven became a freelance journalist specializing in electronics. He is based in

Sydney.

Steven Keeping is a contributing writer

for Mouser Electronics and gained a BEng (Hons.) degree at Brighton University, U.K., before working in the

electronics divisions of Eurotherm and BOC for seven years. He then joined Electronic Production magazine and

subsequently spent 13 years in senior editorial and publishing roles on electronics manufacturing, test, and design

titles including What's New in Electronics and Australian Electronics Engineering for Trinity Mirror, CMP and RBI in

the U.K. and Australia. In 2006, Steven became a freelance journalist specializing in electronics. He is based in

Sydney.

India

India